Published:

Author: Antonio Maria Guerra

Champagne Wine

Many think that Champagne is the best sparkling wine in the world. Is it true? As usual, much depends on personal tastes, but its incredible reputation is undeniable: a popularity grown over the centuries. Let’s try to understand what makes this wine a myth. Let’s find out its history, its places, and its people. Let’s meet Dom Perignon: the monk usually considered the inventor of this specialty.

The history of Champagne wine.

The history of Champagne cannot be told without referring to Dom Perignon. The information we have about him are not very accurate, as it often happens when dealing with a myth. For example, many think that he was an alchemist: something that, in truth, is very unlikely. Despite the lack of reliable sources, it’s possible to figure out, with a certain approximation, who really was the man that, still today, is widely considered the inventor of Champagne.

The assignment in Hautvillers In 1668 the young Benedictine monk Pierre Perignon was transferred to the Abbey of Hautvillers, in the northeast of France. He was assigned with the important task of managing the vineyard and the cellars. This role was particularly appropriate for him since he already had a very good experience in this field: his parents were wine producers and he had spent a great part of his childhood between the rows.

In 1668 the young Benedictine monk Pierre Perignon was transferred to the Abbey of Hautvillers, in the northeast of France. He was assigned with the important task of managing the vineyard and the cellars. This role was particularly appropriate for him since he already had a very good experience in this field: his parents were wine producers and he had spent a great part of his childhood between the rows.

Read more

Dom Perignon and the second fermentation of wine Even if it could seem strange, especially considering who we’re talking about, recent studies show that Dom Perignon, during the early years at the abbey, was committed to prevent, rather than encourage, the beginning of the second fermentation, the process normally used to make Champagne. His task was to find a way to avoid its dangers: it seems that the abbot himself gave him this assignment since he was worried about the explosions that put at risk the safety of his bottles and of the monks working in the cellar. Pierre succeeded: his discoveries allowed him not just to stop the second fermentation but also to control it, mastering its secrets. Thanks to this knowledge he became very expert in the procedure of making sparkling wine, using a method known as ‘Champenoise’ or ‘traditional’. It’s very important to remember that he was greatly helped by the invention of more resistant bottles and by the use of cork stoppers.

Even if it could seem strange, especially considering who we’re talking about, recent studies show that Dom Perignon, during the early years at the abbey, was committed to prevent, rather than encourage, the beginning of the second fermentation, the process normally used to make Champagne. His task was to find a way to avoid its dangers: it seems that the abbot himself gave him this assignment since he was worried about the explosions that put at risk the safety of his bottles and of the monks working in the cellar. Pierre succeeded: his discoveries allowed him not just to stop the second fermentation but also to control it, mastering its secrets. Thanks to this knowledge he became very expert in the procedure of making sparkling wine, using a method known as ‘Champenoise’ or ‘traditional’. It’s very important to remember that he was greatly helped by the invention of more resistant bottles and by the use of cork stoppers.

Dom Perignon and the ‘cuvèe’ Most probably the unique true talent of Dom Perignon consisted in his innate ability to recognize and understand the characteristics and the quality of grapes. Thanks to this natural gift and to his competence, he was able to create some of the great cuvée (*1) that make Champagne so famous in the world: from this point of view, he can really be considered the ‘father’ of this incredible wine.

Most probably the unique true talent of Dom Perignon consisted in his innate ability to recognize and understand the characteristics and the quality of grapes. Thanks to this natural gift and to his competence, he was able to create some of the great cuvée (*1) that make Champagne so famous in the world: from this point of view, he can really be considered the ‘father’ of this incredible wine.

He is widely celebrated still today: for example, the famous winery Moët & Chandon of Epernay, has given his name to one of its best products.

Note:

*1: The French word ‘cuvée’ has several meanings: one of them indicates a blend of wines.

In this article will be explained the production method used to make Champagne wine. You can read its content by clicking this LINK.

Champagne wine in a painting.

The painting ‘Le Déjeuner d’huîtres’, made in 1735 by the French artist Jean-François de Troy and representing a toast during a nobleman’s feast, is very important in the history of Champagne because it’s the first showing some bottles of this wine.

Champagne wine: places and grapes.

The most famous sparkling wine in the world takes its name from a beautiful region in the northeast of France.

Sweet hills surrounded by ordered rows of vines, give life to an incredibly beautiful landscape: in this charming place, during the centuries, grapes and soil have developed a deep connection. That’s why true Champagne can be produced only here. It’s not just a ‘formality’: the particular nature of the local terrain, its exposure and the climate (all aspects of the ‘terroir’), give to this wine its unique characteristics.

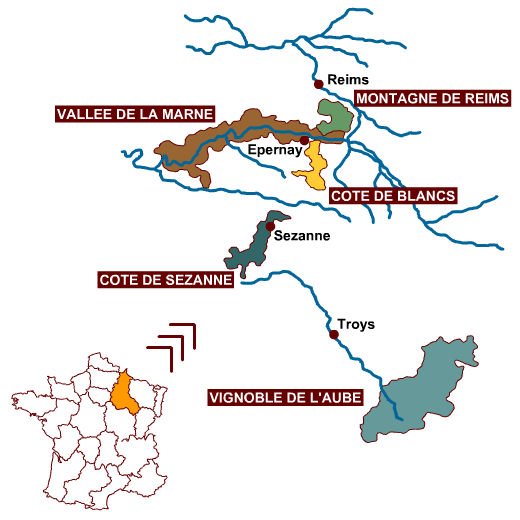

Here follows a brief list of the largest and most famous production areas of Champagne:

Read more

Montagne de Reims

Montagne de Reims

Even if its name is ‘Montagne’ (mountain), there are only sweet hills in this area, not higher than three hundred meters. A Pinot Noir of great quality is produced from the grapes cultivated on their gentle slopes.

Vallée de la Marne

Located just south of the ‘Montagne’, Vallée de la Marne is the largest production area in the Champagne region. There are three types of soil here: chalky, calcareous and clay. This zone is famous for its Pinot Meunier.

Cote des Blancs

This area takes its name from the color of its white grapes (‘blanc’ means ‘white’). A great Chardonnay, a fundamental part of a great ‘cuvèe’, is produced in this zone.

Cote de Sézanne

Located south of the Cote des Blancs, Cote de Sezanne is important for the production of Pinot Noir.

Aube

This area, also known as Cote de Bar, is just south of the beautiful town of Troyes. Its soil is rich in limestone. This zone is famous for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

The right glass for Champagne wine.

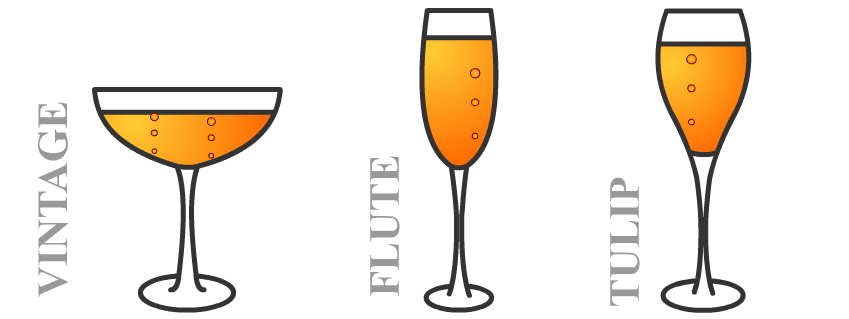

Over the years many have debated about the right glass for Champagne.

Continua

Although the ‘coup’ comes up a lot, professionals agree that to really appreciate this wine, it’s necessary to use an elongated glass, like the ‘flute’ or the ‘tulip glass’.

Their shape, in fact, allows the bubbles to rise, channeling the aromas into a small area, concentrating them to the benefit of the taster’s smell.

Champagne wine: pairings.

Champagne is the perfect match for many kinds of food, for example shrimps:

Read more

- Its acidity and saltiness balance their sweet tendency.

Another very good pairing is with Parmigiano Reggiano:

- Its acidity balances the sweet tendency of the cheese.

- Its effervescence and saltiness balance the fat of Parmigiano.

The English contribution.

It’s quite surprising to find out how old and deep is the connection between the British and Champagne. Two English personalities, in particular, had a very important role in the evolution of this wine between the 16th and the 17th centuries.

Cristopher Merret (1614 – 1695) In 1662 the English scientist Christopher Merret presented to the Royal Society the treaty ‘Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines’, in which he was the first to show the connection between the addition of sugar to wine and the beginning of the second fermentation. He essentially theorized the ‘Champenoise’ method many years before the studies of Dom Perignon.

In 1662 the English scientist Christopher Merret presented to the Royal Society the treaty ‘Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines’, in which he was the first to show the connection between the addition of sugar to wine and the beginning of the second fermentation. He essentially theorized the ‘Champenoise’ method many years before the studies of Dom Perignon.

Sir Robert Mansell (1573–1656) Sir Robert Mansell, Admiral of the Royal Navy and member of the British parliament, was the first to mass-produce a kind of bottle that could resist to the high pressure generated by the carbon dioxide present in the Champagne.

Sir Robert Mansell, Admiral of the Royal Navy and member of the British parliament, was the first to mass-produce a kind of bottle that could resist to the high pressure generated by the carbon dioxide present in the Champagne.

Its ‘secret’ was in the thickness and in the quality of glass, made stronger by the intense heat of coke ovens, much warmer than those burning wood.

The breast of the marquise.

Even if the ‘flute’ is widely considered the best type of glass to serve Champagne, since its elongated form allows a perfect view of the ‘perlage’ (the bubbles), this sparkling wine is often served in the ‘coupe’.

Read more

Legend wants that its particular shape was inspired by the breast of the Marquise de Pompadur, the beautiful lover of King Loius XV of France, the ‘Sun King’.

Copyright information.

The images displayed in this page belong to WebFoodCulture, with the exception of:

Public Domain images

- Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, Jean-Marc Nattier 1746 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

- ‘Le Déjeuner d’huîtres’ di Jean-François de Troy, Jean François de Troy, 1735 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

- Christopher Merret (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

- Sir Robert Mansell (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

Creative Commons images

- Hautvillers Abbey, October Ends (Wikipedia Link);