Published:

Author: Antonio Maria Guerra

The History of Panettone

ORIGIN, LEGENDS AND INTERESTING FACTS

To explore the history of panettone bread is to plunge into a distant past, closely linked to the city of Milan. In this article, we will discover not only the origins but also the legends and the secrets of an exquisite specialty that, over the centuries, has become the culinary symbol of Christmas in Italy. Let’s enrich the whole thing with many fascinating curiosities. Enjoy reading!

The legends about panettone bread.

Many are the legends about the birth of panettone bread. Although a lot of them are far from being true and certainly do not help to establish the exact origins of this Christmas dessert, they undoubtedly have the merit of enriching its appeal and, consequently, its taste. Let us therefore discover some of the most famous and interesting.

The “Pan di Toni”.

The most famous legend takes place in the 15th century, at the court of Ludovico Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan. According to the story, during a large Christmas banquet, the nobleman’s cook, distracted by a thousand tasks, burned the cake, making it de facto inedible. No small incident, especially considering the importance of the guests, which was unexpectedly remedied by a young man named Toni. The boy, little more than a dishwasher, the previous morning had prepared for himself a loaf of bread, using the few ingredients available: eggs, butter, flour, candied fruit, and sultanas. This bread, which unexpectedly became the last hope to solve the embarrassing situation, was served to the guests, who liked its taste so much that they asked the Duke about it. The court cook, quite reluctantly, had to admit that it was the “pan del Toni” (the cook’s exact words would have been “it’s Tony’s bread” – “l’è il pan del Toni”).

Messer Ulivo’s panettone.

Another legend tells of a falconer named Messer Ulivo who, after falling in love with a baker’s daughter, changed his profession and began working for the girl’s father. To show his affection, he prepared a sweet bread with eggs, sugar, butter, flour and sultanas. Messer Ulivo’s ‘panettone’ was so delicious and successful that he was allowed to marry the desired woman.

Sister Ughetta’s panettone.

The third legend tells of Ughetta, a nun who invented panettone to please her sisters. Although this story is the least famous of the above, it’s worth noting that in the Milanese dialect the word “ughett” means “sultana”, which happens to be one of the main ingredients of the Christmas bread we’re talking about.

Let’s find out everything there is to know about panettone bread, from preparation to variations, from calories to pairings … and much more, in the article we have dedicated to the sweet Christmas speciality.

Where was panettone born?

The city of Milan can be considered the ‘cradle’ of Panettone. In fact, it was here that this specialty began an evolution that lasted many centuries, starting in the Middle Ages (although some experts argue that it began even earlier). Located in the Lombardy region, this center plays an important role in the local economy and is the undisputed capital of Italian fashion and design.

The history of panettone: the true origins.

As you can easily imagine, the older a gastronomic specialty is, the more difficult it is to pinpoint its exact origins, making it difficult, if not impossible, to establish the true date of birth. Panettone bread is no exception: its recipe and appearance, as we know them today, are the result of centuries of evolution, with the city of Milan as the only certain point of reference.

Celts and Romans: According to some scholars, the ancient Celtic tribe responsible for founding today’s Milan, the Medhelans, may have tasted a primitive form of panettone (*1) as early as the 6th century BC. Others point to the similarity of this cake with a particular type of bread, very rich in ingredients, prepared by the Romans in classical times. The information available is undoubtedly vague but, at least, it helps us to understand how old the tradition of this Christmas specialty may be.

The Middle Ages and the Renaissance: Various historical documents testify that in the 13th century, the wealthiest inhabitants of Milan enjoyed the ancestor of panettone: a large loaf of bread enriched with various ingredients. In one of his writings at the end of the 15th century, Giorgio Valagussa, a humanist and tutor to the Sforza family, refers explicitly to “three large loaves” (“tre grossi pani”) of wheat bread (*2) that each head of a family would cut on Christmas Eve, during the so-called “rite of the log” (“rito del ciocco”) (*3), distributing the slices among the family members and keeping one as a good omen.

16th and 17th centuries: Between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century, the ‘Varon milanes de la lengua de Milan’, an etymological dictionary of the Milanese dialect written by Giovanni Capis, was published. This dictionary is interesting for the explicit reference to the ‘panaton de Danedaa’: “Pan grosso, quale si suole fare il giorno di Natale, per metafora un inetto, infingardo, da poco” (“Large loaf, such as is customary on Christmas Day …”). Another very interesting testimony about panettone can be found in a note still preserved in the Collegio Borromeo in Pavia, a town not far from Milan. This note, dated 1599, specifies the ingredients needed by the baker to prepare the “13 pani grossi per dar alli scolari il giorno di Natale” (“13 large loaves to be given to schoolchildren on Christmas Day”): butter, sultanas, and spices.

1814, Cherubini’s ‘panatton’: In 1814, the Milanese man of letters Francesco Cherubini began writing his Vocabolario Milanese-Italiano (Milanese-Italian Vocabulary), a text of fundamental importance in the history of panettone, as it was the first to give a precise definition of the specialty: “A type of bread decorated with butter, sugar and raisins or currants (ughett), which is made in various forms in our city at Christmas, which is why it is also called ‘el panatton de Natal’ among us”.

Notes:

*1: During the traditional Yule celebrations held every year in December to mark the winter solstice;

*2: Wheat bread was highly prized and intended exclusively for the nobility and the wealthy.

*3: The ‘Rito del Ciocco’ (‘Ritual of the Log’), to which Valagussa refers, is described in more detail in one of the sections of this article.

The origin of the name panettone.

There are several hypotheses on the origins of the name ‘panettone’ (in the Milanese dialect ‘panetùn’). Here is a short list of them:

Read more

Being a ‘big bread’, the term could be an augmentative of the Italian word ‘pane’: ‘panettone’;

‘Panettone’ could come from ‘pan de ton’, an expression used in Milan in the 15th century to indicate the bread for the rich, i.e. white bread, quite different from the ‘pan de mei’, intended for the common people;

If we want to believe the most famous legend about the invention of the panettone (explained in this article), the name could come from ‘Pan de Toni’

The history of panettone: the ‘rite of the ciocco’.

The ‘rite of the ciocco’ (log) was once a very popular tradition in Milan: on the evening of Christmas Eve, each head of the family, after sprinkling wine on a large wooden branch (the ‘ciocco’), would throw it into the fireplace for it to burn.

Read more

Once this was done, he would cut “tre grandi pani” (“three large loaves”) into slices, distributing them among the family members and keeping one for the next day as a sign of good fortune. It’s quite possible that these “large loaves” were nothing more than a a primitive form of panettone bread.

Count Pietro Verri, historian, philosopher and economist, describes the ritual in the first volume of his ‘History of Milan’, published in 1836:

“On the eve of Holy Christmas, a log adorned with leaves and apples was burnt, wine and juniper were sprinkled on it three times, and the whole family celebrated around it. This custom still lasted in the tenth-fifth century, and was celebrated by Galeazzo Maria Sforza. On Holy Christmas Day, the fathers of the family distributed money so that everyone could have fun playing games. On those days, large loaves of bread were eaten, and chickpeas, ducks and pork were placed on the table, as people do nowadays”

The history of panettone: the panettone of St. Biagio.

It’s interesting to find out that there is an old Milanese tradition according to which, during the Christmas festivities, a portion of panettone should be put aside to be eaten a few weeks later, the 3rd of February, the day Saint Blaise is celebrated.

Read more

This is to commemorate the day when the saint is said to have saved a young man who was about to choke on a fishbone stuck in his throat by making him swallow breadcrumbs. Since then, it has been widely believed that eating panettone on the 3rd of February can actually protect the health, especially that of the respiratory system.

In this regard, there is a famous saying in the Milanese dialect: “A San Bias se benedis la gola e él nas” (“at St Blaise’s you bless your throat and nose”).

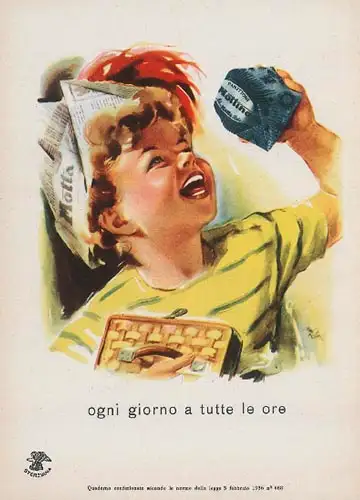

The importance of Motta in the history of panettone.

Perhaps not everyone knows that Motta, one of Italy’s most famous confectionery companies, has played a huge role in the history of panettone, contributing significantly to its success. It’s credited with transforming a local artisanal specialty into an icon of Italian taste, much appreciated worldwide. The secret of its wide diffusion lies in the standardization of the recipe and of the shape, but above all in its industrialization: from the first half of the 20th century onwards, this allowed an exponential increase in the production of panettone, which year after year reached an ever wider clientele.

Nor should we forget the fundamental role of communication, to which Angelo Motta (founder of the company) attached great importance, both in terms of advertising (posters, commercials, etc.) and marketing (logo, packaging, etc.). It was precisely the effectiveness of this communication, which was innovative in many ways, that trasformed the dessert into an undisputed symbol of the Christmas holidays.

Motta: the sweet, in Milan.

Motta, one of Italy’s most famous confectioners, was born in Milan in 1919 when Angelo Motta founded ‘Angelo Motta Pasticciere’ in a small workshop in Via della Chiusa. Right from the start, one of the company’s flagship specialties was the ‘panettone’: a symbol of the local gastronomic tradition. The success of this specialty was such that, in 1925, Mr Angelo opened a second workshop in Via Carlo Alberto, followed by a shop in 1928. In 1930 the company changed its name to ‘Dolciaria Milanese’ and in 1937 it became Motta S.p.a.

Read more

Also in the 1930s, thanks to the intuition of a brilliant publicist, Dino Villani, the success story of the Colomba cake began.

The fifties were particularly important, with the creation of the ice cream department and the launch of the famous Mottarello. 1954 saw the birth of Buondì, considered the first Italian sweet snack. After Angelo died in 1957, Motta passed into the hands of Alberto Ferrante until it was acquired by SME, which in 1976 announced the merger with Alemagna to form Unidal. Since 2009, Motta’s baked goods business belongs to Bauli S.p.a.

The history of panettone: Prince Metternich loved panettone bread.

Prince Klemens von Metternich was one of the most important admirers of panettone bread (as well as Sachertorte). For this reason, during the Austrian domination of Milan, the governor of the city, Ficquelmont, used to give him this specialty as a holiday gift. It is also said that the prince, referring to the Milanese who took part in the ‘5 Giornate’ (‘five days’) revolts, exclaimed: “sono buoni come i panatoni!” (“They are as good as panatoni!”).

The history of panettone: a panettone for Pope Pius IX.

In 1847, Paolo Biffi, confectioner to the House of Savoy, prepared a large panettone bread to give ad a gift to Pope Pius IX. He then arranged for the Christmas specialty to be delivered to Rome as quickly as possible in a special carriage.

Motta: contacts.

This article was made in collaboration with Bauli S.p.a., the company that owns the brand of Motta, the historical producer of panettone bread.

Contacts

Address: Bauli S.p.A – Via Verdi 31 – 37060 Castel d’Azzano (VR) – Italia

Web:https://www.bauli.it/

Tel. : 800 888 166

Copyright information.

The images displayed in this page belong to WebFoodCulture and Bauli S.p.a., with the exception of:

Public Domain Images:

- Pope Pio IX, George Peter Alexander Healy 1871 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

- Metternich, 1834 / 1840 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art}

- Saint Blaise, Hans Memling, 1491 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- Milan topography, 1573 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- Francesco I Sforza, B.Bembo, XV sec. (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- First pastry workshop founded by Angelo Motta in via della Chiusa (Milano) in 1919 (Wikipedia Link)

Creative Commons Images:

- Piazza Mercanti, Milan, Stefano Stabile (Wikipedia Link)

- Milan, Scrofa Seminaluta, image owner: Bramfab (Wikipedia Link)