Published:

Author: Antonio Maria Guerra

Venetian Frittelle

HISTORY, PLACES, INFO, INTERESTING FACTS

The history of the Venetian frittelle, known in dialect as ‘fritole’, has its roots in the distant past, long before the Serenissima became a great maritime power. These delicacies, which characterize the Carnival celebrations in the lagoon city, are full of tradition and legend. Let’s find out together the reason for their charm. Enjoy reading!

The history of Venetian frittelle.

It’s almost impossible to establish with certainty the date of birth of the frittella (fritter). As is often the case with specialties from the Italian peninsula, some scholars trace its origins back to ancient Rome, where a vaguely similar preparation was eaten: the ‘globulos’ (*1).

References to something alike are can also be found in a 14th century document (*2), the authenticity of which has yet to be established.

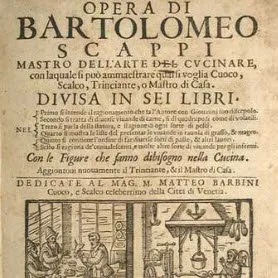

One of the first certain testimonies dates back to the Renaissance and is included in the treatise on cooking (*3) written by Bartolomeo Scappi, ‘master in the art of cooking’ and cook to Popes Pius IV and Pius V. In this monumental work, Scappi illustrates many recipes for sweet and savory fritters, including the ‘frittella alla venetiana’: it’s no coincidence that this delicacy was so successful in the Serenissima Republic that it became the ‘national dessert’ in the 18th century.

Notes:

*1: The ‘globulos’, described in detail in a section of this article, were consumed during the Saturnalia celebrations.

*2: A codex said to survive in the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome.

*3: ‘Opera di M. Bartolomeo Scappi, cuoco secreto di Papa Pio V’, 1570.

Venice: the cradle of the frittelle.

Venice, the ‘cradle’ of the frittelle, is located in the Italian region of Veneto. Its foundation dates back to 421 A.D., as proven by archaeological excavations at Riva Alta (today’s Rialto area). The city grew from a settlement of refugees fleeing the barbarian invasions to the famous Maritime Republic we all know: a center of power and culture that reached the height of its success in the 15th century, thanks to its role as a commercial bridge between East and West.

The history of Venetian frittelle: who were the ‘fritoleri’?

The ‘fritoleri’ were the artisans who once cooked and sold frittelle (fritters) in Venice, a specialty also known in the local dialect as ‘fritole’ or ‘fritoe’. These peculiar characters were easily recognizable by the wide apron they wore and the jar full of sugar (*1) they waved with colorful gestures to attract the attention of passers-by. Many were itinerant, while the richest had rectangular huts in which they used their ‘tools of the trade’, including large wooden planks and great frying pans. The front of these huts was used to display their delicious preparations. When their frittelle were ready, they carefully arranged them in richly decorated metal plates (*2), surrounded by a selection of the used ingredients, that showed their true quality and made the merchandise even more attractive.

The fritoleri took great pride in their work, so much so that they had their name engraved on a signboard to make them more recognizable. In 1619, to protect their art (and their business), they went so far as to create a proper guild: this way, each of the 70 members was guaranteed a specific area of the city in which to practice their trade, as well as the right to pass on the profession (and its privileges) to their children.

The Guild of the Fritoleri was a very successful institution, so much so that it lasted for more than two hundred years (*4) and was celebrated in many works by famous artists.

Notes:

*1: The use of sugar by the fritoleri is a not insignificant detail to which we have devoted a special section of this article.

*2: This information is taken from the book ‘Scene di Venezia : Municipali suoi costumi’ by Pietro Gasparo Moro (1841).

*3: The ingredients used were flour, eggs, pine nuts, sultanas and candied citron.

*4: Until the end of the 19th century.

‘Globulos’: the ancestors of the Venetian Frittelle.

The ‘Globulos’ are often considered as the true ancestors of the Venetian frittelle. They were prepared in ancient Rome during the ‘Saturnalia’, the festivities held in December in honor of the god Saturn, with a dough made from durum wheat semolina and cheese. This dough was used to shape spherical morsels that were cooked in fat and seasoned with honey and poppy seeds. The full description of their recipe can be found in ‘De agri cultura’, one of the most famous works by Marcus Porcius Cato, a Roman intellectual, politician, and general.

When are Frittelle sold?

In the city of Venice, Frittelle should be sold, at least theoretically, starting from the day after Epiphany, until Mardi Gras. It’s more a habit than a rule, part of an ancient tradition, nowadays frequently disregarded.

The history of Venetian frittelle: sugar, a highly prized product.

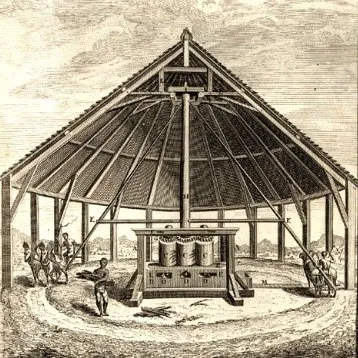

As already mentioned in another paragraph of this article, one of the elements that made the ‘fritoleri’ (the ‘artists of the frittella’), easily recognizable, was the theatrical gestures with which, using a jar, they sprinkled their exquisite preparation with copious amounts of sugar. Such nonchalance, though not surprising today, was once quite remarkable: for many centuries, sugar was indeed a very rare commodity in Europe. It had to be imported from distant lands and was therefore only used as a sweetener only by the wealthy. Ordinary people had to make do with honey, taking care not to overdo its doses.

However, it should be pointed out that the Republic of Venice, especially at the height of its expansion, was an exception in this respect: thanks to its vast trading network, it enjoyed supplies of sugar at much cheaper prices. Much of this relatively ‘affordable’ sugar, came from the colonies, including the island of Crete, at the time known as Candia (*1). It’s therefore no coincidence that Venice developed one of the oldest (and richest) confectionery traditions in continental Europe, of which the ‘fritole’ are undoubtedly a part.

Notes:

*1: The ‘candioto’ sugar (because it was produced in Candia), was used in the production of ‘candii’, the product we now know as ‘candied’ fruit.

The history of Venetian frittelle: Fratelli Rizzardini, the oldest pastry shop in Venice.

WebFoodCulture is in the habit of writing its articles in collaboration with those who can be considered the ‘keepers of tradition’ with regard to the specialities covered. In the case of Venetian frittelle, an unavoidable point of reference is undoubtedly the Pasticceria Fratelli Rizzardini which, not by chance, is the oldest pastry shop in Venice. Founded in 1742, this place was originally known as ‘Lo Scaleter’, with reference to the ancient trade of the ancient Venetian pastry chefs, the ‘scaleteri’ (*1), who specialised in making sweet pastries known as ‘scalete’. In the 19th century, when its ownership passed to a family from Val di Zoldo,

Read more

the shop was renamed with the family name of Rizzardini. This ‘temple of taste’, which still retains its splendid ancient furnishings, is located in the San Polo district, in the heart of the lagoon city. For almost three centuries it has been delighting locals and tourists alike with its specialities, among which, in addition to the not-to-be-missed frittelle, we must mention the ‘sanmartini’, typical sweets of 11 November, the ‘focaccia’, a soft and fragrant bread, and the ‘bussolai’ biscuits.

The history of Venetian frittelle: the Venetian Carnival.

Carnival is a celebration that has its roots in the distant past: some scholars trace its origins back to ancient times, even before the Roman ‘Saturnalia’ and the Greek ‘Dionysia’: events very similar in many ways. What unites all these festivities is the spirit of renewal that recurs at the beginning of each year. This renewal takes the form of a temporary suspension of the rules in favor of chaos, considered to be the generative force par excellence.

A kind of ‘beneficent disorder’, staged by the carnival as in a play, which allows normally forbidden excesses and a temporary subversion of the social order, thanks to which, for a few days, the poor are allowed to ‘dress up’ as the rich and vice versa (*1).

As it’s easy to understand, masks play a fundamental role in this great game. Among the most beautiful are those of Venice, where culture, fantasy, and color come together in an admirable way, also thanks to the mastery of skilled craftsmen.

Carnival has been celebrated in the city since 1094 (*2), and it has a particular charm thanks to the evocative beauty of its places, its perfumes, and its flavors. Smells and tastes that can be found, for example, in certain sweet specialties that are prepared only during this festivity: the ‘fritelle’ (in dialect ‘fritole’ or ‘fritoe’) and the ‘galani’.

Read more

It’s easy to understand why masks play a fundamental role in this great game.

Those made in Venice are among the most beautiful: a true form of art, blending culture, imagination and colors, thanks to the virtuosity of skilled craftsmen.

Carnival has been celebrated in the city since 1094 (*2): a city famous worldwide for the beauty of its places, for its scents and its flavors. Perfumes and flavors that can be found, for example, in particular pastry specialties, prepared only during this festivity: ‘Frittelle’ (‘Fritole’ or ‘Fritoe’) and ‘Galani’.

Notes:

*1: The special freedom granted to the people (anyway subject to strict monitoring), had the great advantage to be a sort of ‘safety valve’ for social tensions.

*2: The first document containing a reference to the Venetian Carnival, dates back to the year 1094 and was written by the famous Doge Vitale Falier.

The etymology of the word ‘Carnival’.

There are several theories about the origins of the word ‘Carnival’ (in Italian, ‘carnevale’). According to the most accredited one, it could derive from the fusion of two Latin terms: ‘carnem’ (‘meat’) and ‘levare’ (‘remove’), with reference to the habit of starting a period of abstinence from meat immediately after ‘Mardi Gras’ (‘Martedì Grasso’), the closing day of the festivity.

Copyright information.

The images displayed in this page belong to WebFoodCulture, with the exception of:

Public Domain images

- ‘Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi …’, B.Scappi, XVII sec. (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- ‘Venditrice di frittelle’, Pietro Longhi, 1757 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- Sugar mill, XVIII sec. (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- ‘Santi Giovanni e Paolo e la Scuola di S.Marco’, Canaletto, 1726 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- ‘S. Geremia e l’ingresso di Cannaregio’, Canaletto, 1727 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- ‘Piazza San Marco’, Canaletto, 1730/34 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}

- ‘Il Bucintoro attraccato nel giorno dell’Ascensione’, Canaletto, 1740 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-Art} {PD-US}