Published:

Author: Antonio Maria Guerra

World War I Food

An army marches on its stomach”: this statement, attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte, shows how clear to him was the importance of soldiers’ nutrition to the tide of an armed confrontation, on a par with their training and equipment. The correctness of his assertion was proven, among other things, during the first great conflict of the modern age: let’s find out World War I Food.

The First World War.

The First World War began on 28 July, 1914. The spark that led to the explosion of the conflict was an attack in the city of Sarajevo: a tragic event where the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife were assassinated by a political extremist. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, considering the Kingdom of Serbia responsible for what happened, began the hostilities. The golden age of Europe, the ‘Belle Epoque’, had to give way to a clash of nations of unprecedented proportions: that’s why it’s still remembered as the ‘Great War’.

The First World War began on 28 July, 1914. The spark that led to the explosion of the conflict was an attack in the city of Sarajevo: a tragic event where the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife were assassinated by a political extremist. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, considering the Kingdom of Serbia responsible for what happened, began the hostilities. The golden age of Europe, the ‘Belle Epoque’, had to give way to a clash of nations of unprecedented proportions: that’s why it’s still remembered as the ‘Great War’.

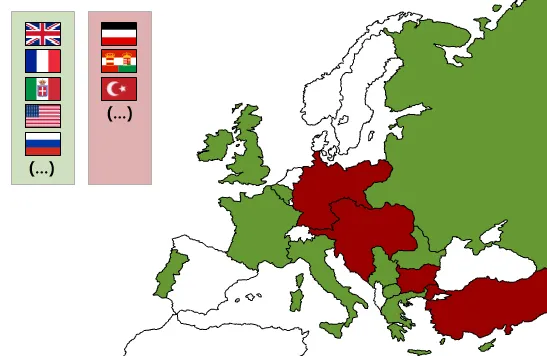

The warring sides. A complex system of alliances gradually involved in the hostilities a great number of countries. The two warring sides were:

A complex system of alliances gradually involved in the hostilities a great number of countries. The two warring sides were:

- he Central Powers, including (among the others) the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire;

- The Allies, including (among the others) France, the British Empire, the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Serbia. These were later joined by the Empire of Japan, the Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Romania, the United States and the Kingdom of Greece;

Read more

The causes.

It’s important to stress the fact that the attack in Sarajevo was just a triggering event, the final step of a complex situation worsened over the years. The real causes of the war were many, among them:

- The desire of the German Empire to play a strong political role on the international stage;

- The necessity of the authoritarian regimes to harness the socialist movements threatening their power;

Trench warfare. A quick attack by the German Army to the Netherlands and to Northern France, seemed to decide the outcome of the conflict a few months after its beginning. The Central Powers tried their best to achieve a fast victory, quite aware of the many unknowns associated to a prolonged war effort. Their hopes were shattered by the fierce resistance of the French troops. The advance was stopped during the famous Battle of the Marne. The soldiers of both sides had to take refuge in trenches dug along a never ending frontline: a bloody and grueling war of attrition had just begun.

A quick attack by the German Army to the Netherlands and to Northern France, seemed to decide the outcome of the conflict a few months after its beginning. The Central Powers tried their best to achieve a fast victory, quite aware of the many unknowns associated to a prolonged war effort. Their hopes were shattered by the fierce resistance of the French troops. The advance was stopped during the famous Battle of the Marne. The soldiers of both sides had to take refuge in trenches dug along a never ending frontline: a bloody and grueling war of attrition had just begun.

The lack of food. Fields were devastated by the fury of battles or abandoned by farmers forced to join the army. This caused a considerable reduction in agricultural production. The resulting food shortages were further aggravated by naval blockades and submarine attacks, preventing any attempt to get supplies. The Central Powers found themselves in serious trouble, even more than the Allied Nations. Their resources were in fact extremely limited and in great part used to support soldiers. In the cities people started to die of hunger: malnutrition killed thousands, causing numerous revolts.

Fields were devastated by the fury of battles or abandoned by farmers forced to join the army. This caused a considerable reduction in agricultural production. The resulting food shortages were further aggravated by naval blockades and submarine attacks, preventing any attempt to get supplies. The Central Powers found themselves in serious trouble, even more than the Allied Nations. Their resources were in fact extremely limited and in great part used to support soldiers. In the cities people started to die of hunger: malnutrition killed thousands, causing numerous revolts.

The United States of America enter the war. It’s important to stress the fact that the German and Austrian armies found themselves facing an enemy that instead of weakening was getting stronger day after day. The entry of the United States into the conflict marked the definitive turning point: the large number of fresh troops and the enormous quantity of supplies that were poured onto the war chessboard led to the definitive defeat of the Central Powers

It’s important to stress the fact that the German and Austrian armies found themselves facing an enemy that instead of weakening was getting stronger day after day. The entry of the United States into the conflict marked the definitive turning point: the large number of fresh troops and the enormous quantity of supplies that were poured onto the war chessboard led to the definitive defeat of the Central Powers

How and what did the soldiers of the factions engaged in the Great War eat? Let’s find out in this article LINK.

Sir Winston Churchill writes home.

Perhaps not everyone knows that Sir Winston Churchill, the famous British Prime Minister who contributed to defeat Adolf Hitler in the Second World War II, was involved also in the first,

Read more

as Commander of the Sixth Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

During the conflict, he wrote numerous letters to his wife: these letters are interesting not only because they reveal the human side of the statesman, but also because they show how frequently soldiers and officers asked their families for food. Something they had to do, since their military rations were generally insufficient to survive.

Here follows a brief excerpt from one of his letters:

“ … about food, the sort of things I want you to send me are these: large slabs of corned beef, stilton cheeses, cream, hams, sardines, dried fruits. You might almost try a big beef steak pie but not tinned grouse or fancy tinned things. The simpler the better and substantial too, for our ration meat is tough and tasteless, and here we cannot use a fire by daylight. I fear you find me very expensive to keep. Mind you bill me for all these apart from your housekeeping … ”.

World War I food: hardtacks in soldier’s pockets.

The ‘hardtack’ is an incredibly simple type of biscuit, made just with flour, water and sometimes a little bit of salt (*1).

Read more

Its origins are very ancient: it was already known to the Egyptians. The Romans called it ‘buccellum’.

The great success of this food is due to its long keeping: if kept away from water and humidity, it can remain edible for many years. Thanks to this useful feature, it has always been part of the rations of soldiers and sailors.

The French call it ‘galet’ (small stone), the Italians ‘galletta’, the Germans ‘schiffszwieback’.

Note:

*1: No yeast is used to make hardtacks.

The ‘Great War’: a new kind of conflict.

To understand how much feeding troops tipped the balance of power during the Great War, it’s important to explain first the huge difference between this conflict and the previous ones. The hostilities broke out in 1914, involving, one after the other, a great number of nations. The almost romantic idea, legacy of the Napoleonic era, of opposing armies fighting each other with honor, vanished almost immediately. When the first charge of heavy cavalry, until then considered the most powerful weapon, was easily annihilated by machine-guns, it became clear to everyone that something was definitely changed and it was thus necessary to completely rethink the way of fighting. After a few attacks of this type, the frontline stabilized.

To understand how much feeding troops tipped the balance of power during the Great War, it’s important to explain first the huge difference between this conflict and the previous ones. The hostilities broke out in 1914, involving, one after the other, a great number of nations. The almost romantic idea, legacy of the Napoleonic era, of opposing armies fighting each other with honor, vanished almost immediately. When the first charge of heavy cavalry, until then considered the most powerful weapon, was easily annihilated by machine-guns, it became clear to everyone that something was definitely changed and it was thus necessary to completely rethink the way of fighting. After a few attacks of this type, the frontline stabilized.

Troops, desperately seeking refuge from new, deadly weapons, found shelter in the trenches: deep holes in the ground, dug along the margins of the opposing battle lines.

A huge, monstrous serpent, cut Europe in half, from north to south.

World War I food: ‘erbswurst’, so much more than a sausage.

Before the beginning of the Great War, the Generals of the Kaiser tried to find a way to feed their troops, at the same time ensuring them maximum mobility.

Read more

This was in fact essential for the ‘blitzkrieg’, the ‘lightning war’ they were planning. The ‘Erbswurst’ came up as the answer to their needs: it was a particular type of sausage, made with a mixture of dried bacon and pea powder. This sausage, cut in thick slices, could be rehydrated in hot water, preparing in a few minutes a nutritious and tasty soup. Its inventor was Heinrich Grueneberg: in 1899 he sold the patent to the famous food company Knorr.

The Erbswurst is produced still today.

World War I food: the huge importance of food during the Great War.

The commanders of both sides involved in the conflict, initially thought that their troops were going to stay in the trenches just for a brief period: they were wrong. Soldiers had in fact to remain inside of them for many years, killed in great number during frequent attacks to enemy positions: offensives as bloody as useless. What the generals planned as a short confrontation that would ensure a fast and glorious victory, turned into a nightmare: a long and grueling war of attrition. Among other things, it became quite clear that it was necessary to create a reliable system to feed a large number of men.

Food was usually prepared in field kitchens located in the rear, places sometimes very distant from the endless front line: it was therefore inevitable that, after a long and difficult transport, rations reached their destinations in terrible conditions. The quantity and quality of these rations, aspects initially underestimated, proved instead to be crucial for the war effort: something that could affect the morale and the performance of soldiers, greatly influencing their combat effectiveness.

It became evident that the faction that could better feed its troops, in the end would probably win the war.

Food acquired a fundamental role, becoming a kind of weapon, perhaps even the most effective. So it’s no coincidence that both sides tried to destroy enemy supplies whenever it was possible.

World War I food: ‘the use of alcohol in the trenches.

During the Great War, alcohol was not allowed in the trenches, at least officially.

Read more

In particular situations, when an extra dose of courage was needed, a few exceptions were tolerated: for example, before an assault, some ‘grappa’ (an alcoholic beverage) was distributed to the Italian soldiers.

The songs of the Great War.

Some of the most famous songs at the time of the First World War are probably the best choice to accompany the reading of this article:

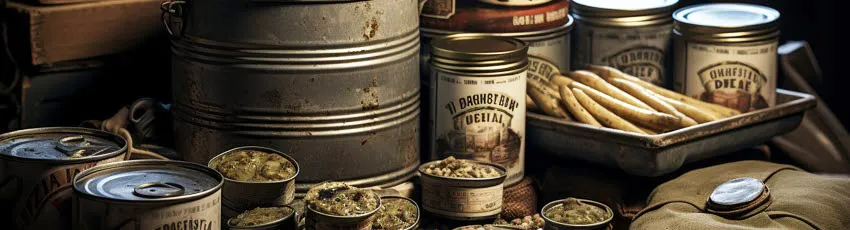

World War I food: the great use of tin cans.

A few months after the beginning of the First World War, it became very clear how complex it would be to provide supplies to troops living and fighting along an endless frontline. The distribution problems were worsened by frequent enemy attacks. Even in a situation difficult like this, it was still necessary to feed soldiers regularly, so that, if not bullets, they could at least survive hunger.

Canned food proved to be the best instrument to feed soldiers when normal rations could not be provided.

Tin cans could contain a wide variety of aliments: meat, fish, butter, soups, ham etc. Their metallic coating and hermetic closure, not only ensured long keeping, but also protected the content from dirt and poisoning caused by lethal gas (*1). Thanks to these particular features, they were often the last resource (*2), that’s why sometimes it was necessary the permission of a senior officer to open them.

During the years of conflict, the armies of both sides used a huge number of tin cans: even today, after more than a century, rusty remnants of them can be found scattered around the old battlefields.

Notes:

*1: Lethal gas was one of the weapons used by the German Army during the Great War.

*2: Soldiers had to carry in their backpack a few tin cans (at least in theory). In some particularly dangerous situations, their life could depend on them.

World War I food: hungry soldiers raid the enemy’s depots.

In March 1918, a great number of German troops, taking advantage of the defeat of the Russian Empire, started to fight on the Western Front.

Read more

Soon after, thanks the ‘Spring Offensive’, they broke through the British lines. The soldiers of the Kaiser, driven by hunger, raided the enemy food storages: it seems that they particularly appreciated canned meat, also known as ‘bully beef’.

World War I food: living in a trench.

At the beginning of the Great War, ‘trenches’ were nothing more than deep holes dug in the ground along the frontlines. Enemy positions were usually at a certain distance, on the other side of the ‘no man’s land’. Even if many generals had predicted fast advances (and victories), during the conflict these frontlines remained stable for a long time

Read more

An unexpected stalemate that forced to transform these simple ditches, initially meant just to protect from artillery fire, into structures complex enough to accommodate thousands of soldiers.

The most common trench was about a meter and a half deep, the side facing the enemy lines was covered with sandbags. For many years, places like this became home to a great number of men. ‘Houses’ offering terrible living conditions. They were cold in winter and incredibly hot during summer. The lack of sewers made them dirty and smelly. When it rained, mud reached the knees. It was almost impossible to wash themselves. Rats and corpses everywhere. Food and water were scarce and awful.

An horrible situation worsened, if possible, by an unstoppable fear to die, shot by the enemy or killed during an assault.

World War I food: Napoleon, Appert and canned food.

It’s quite possible that tin cans would have been very useful to Napoleon Bonaparte in his war campaigns. So, it’s probably not a coincidence that, in a way, he was responsible for their invention, by organizing a contest to find a new method to preserve food.

It’s quite possible that tin cans would have been very useful to Napoleon Bonaparte in his war campaigns. So, it’s probably not a coincidence that, in a way, he was responsible for their invention, by organizing a contest to find a new method to preserve food.

The contest was won by the French chef Nicolas Appert: he created a procedure, the ‘appertisation’ (*1), which consisted in boiling food and sealing it in glass jars (*2).

A few years later another Frenchman, the engineer Philippe de Girard (1775-1845), perfected this procedure by using tin containers. Even if this technique is usually attributed to Peter Durand, many historians think that he was just the first to patent it in the UK and the US (*3). In 1812 the English company Donkin and Hall paid Durand a thousand pounds for the patent and soon became the first tin can producer in the world.

A few years later another Frenchman, the engineer Philippe de Girard (1775-1845), perfected this procedure by using tin containers. Even if this technique is usually attributed to Peter Durand, many historians think that he was just the first to patent it in the UK and the US (*3). In 1812 the English company Donkin and Hall paid Durand a thousand pounds for the patent and soon became the first tin can producer in the world.

Notes:

*1: The procedure invented by Appert was based just on empirical experiments. Some years later, thanks to the research of the French biologist Louis Pasteur, the sterilization process was finally scientifically explained.

*2: The glass containers were usually sealed using pitch.

*3: Durand patented the same procedure twice: the first time in the UK, the second in the United States. In this country the technique was further improved by reducing the time required for its application, from several hours to a few minutes.

How and what did the soldiers of the factions engaged in the Great War eat? Let’s find out in this article LINK.

Copyright information.

The images displayed in this page belong to WebFoodCulture and to Mr. Alessandro Dal Ponte, with the exception of:

Public Domain images

- “Domenica del Corriere”, Sarajevo attack, Beltrame, 1914 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

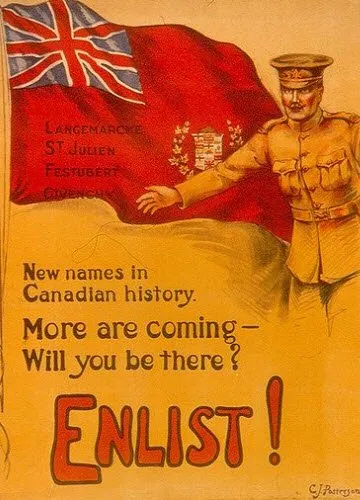

- Canadian WW1 recruiting poster, 1914/1918 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

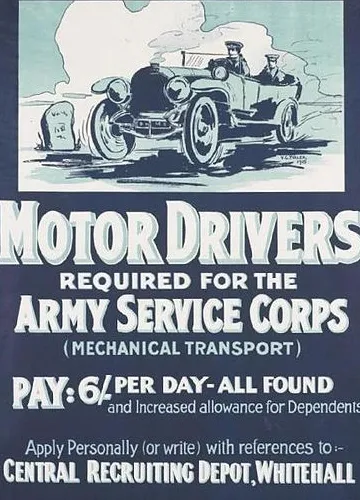

- Army Service Corps recruiting poster, 1915 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

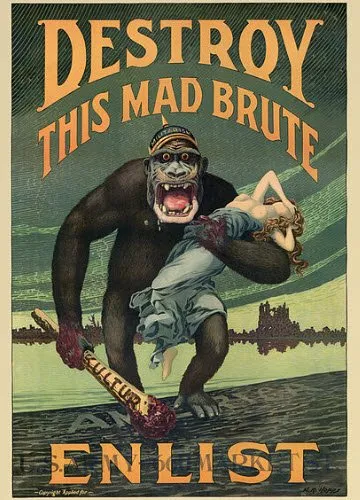

- U.S. Army recruiting poster, 1917, H.R.Hopps (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- U.S. Army recruiting poster, James Montgomery Flagg , 1917 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- Battle of the Somme, trench, 1916 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- Battleship HMS Irresistible sinking, 1915 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- US President Woodrow Wilson asks to the Congress to declare war on Germany, 1917 (Wikipedia Link)

- Portrait of Nicolas Appert, 1841 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- Portrait of Philippe de Girard (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

- Winston Churchill and his squad of fuciliers, 1916 (Wikipedia Link) {PD-US}

Creative Commons images

- Erbswurst, photo by Zenz (Wikipedia Link)